A TALK WITH NIKOLA TESLA

by Frank G. Carpenter

State, The, Columbia, SC

December 18th, 1904

New York, Dec. 17 — I give you today the substance of two remarkable talks with Nikola Tesla. The first I had in his laboratory on east Houston street nine years ago last September. The second was held in the Waldorf tonight.

The first interview was most interesting, giving a wonderful insight into Tesla the inventor and Tesla the man, but it was never published, for Mr. Tesla at its close, for business reasons, begged that I say nothing about him for months to come. I wrote out the notes, however, and laid them away, and when I met Mr. Tesla tonight I told him I how intended to use them. At the same time we had the extraordinary conversation about his recent discoveries and inventions as to the transmission of force, which I reproduce in the latter part of this article.

TESLA THE MAN.

First take a glance at Tesla the man. He looked more like an Italian savant than a hard working inventor when I saw him in the Waldorf tonight. He was in evening dress and was the most striking figure of the score of public men who stood about the lobby. Mr. Tesla is now 47 years of age and is in his physical and intellectual prime. He is tall and slender, his head is long, thin and intellectual, with a forehead high and full. He was born in Hungary and educated there, but he speaks English perfectly and is one of the most charming conversationalists I have ever met.

During my chat of some years ago he talked of his boyhood. His father was a clergyman of the Greek church, and Nikola was intended for the priesthood. He had a brother older than himself, whom the family considered much brighter. That brother died young, and this so crazed his father and mother that it took them long to realize the genius of Nikola. If he stood well in his studies his father's eyes would fill as he thought how much better, perhaps, the other son might have done, and whatever Nikola did was always compared with the possible work of the boy who had passed away. His first education was in the public schools of Gospich, and after that he went to the Real Schule at Karlstadt. As he went on with his studies he liked mathematics so much that he intended to fit himself to be a professor of mathematics and physics, and with that view studied at the polytechnic school at Gratz. He changed to the engineering course, and later on studied philosophy and languages in the colleges at Prague and Budapest. He has since been made a doctor of laws by Yale and Columbia.

Shortly after completing his studies Mr. Tesla was associated with the government of Austria-Hungary in the telegraph engineering department, where he invented several improvements. From there he went to Paris to be engineer of a large lighting company, and thence to the United States, where he was employed by Thomas Edison in his laboratory. His next position was that of electrician to the Tesla Electric Light company, and at the same time he established the Tesla laboratory here, from which his great inventions have come.

TESLA THE INVENTOR.

During my chat with Mr. Tesla I asked him when he first realized that he had the inventive faculty and he told me he had always been inventing something or other. When he was quite a small boy he made toy guns, which would shoot birds, and as he was the only one who could make them he supplied the boys of his neighborhood. He made clocks at eight or nine years and began to dabble in electricity before he was in his teens. His first determination to devote his life to invention came shortly after he went to London to deliver a lecture before a scientific society there. At this lecture he met Lord Rayleigh, the great physicist, and showed him some of the experiments. Rayleigh said that he had, undoubtedly, the faculty of discovery and that he would succeed as an inventor.

“Shortly after this my mother died,” said Mr. Tesla, “and I concluded to exert this faculty. Lord Rayleigh had said I possessed it and, upon examining myself, I believed him correct. I did not want to waste my powers on small things and I decided to strive toward something that would benefit humanity. I am working on an invention for the transmission of force. This invention will, I believe, revolutionize the world of labor. I am also working on electricity and I cannot remember when I was not working more or less in the direction of a successful flying machine. My idea, as to that, is along different lines than any yet proposed and I expect to see it realized. Indeed, we shall eventually have flying machines that will be large enough to carry crowds through the air. They must be large in order to succeed.”

These words were uttered by Mr. Tesla nine years ago. Today he says he has completed his force transmission invention, as will be seen by my Waldorf conversation, which follows. He has also done other things which he proposed in that interview. Remember it was before the time of the wireless telegraph, but he then said to me the following:

“I tell you, we are on the threshold of a new era. We have only begun to master the great forces of nature, and the inventions of the next few decades will be far superior to any of the past. What would you think of standing on the shore and telephoning to your friends in midocean? What of being in the centre of a room and making your whole body blaze with light? What of sending power to and fro over the earth at will and making it do its work anywhere and almost anyhow?

HOW IT FEELS TO INVENT.

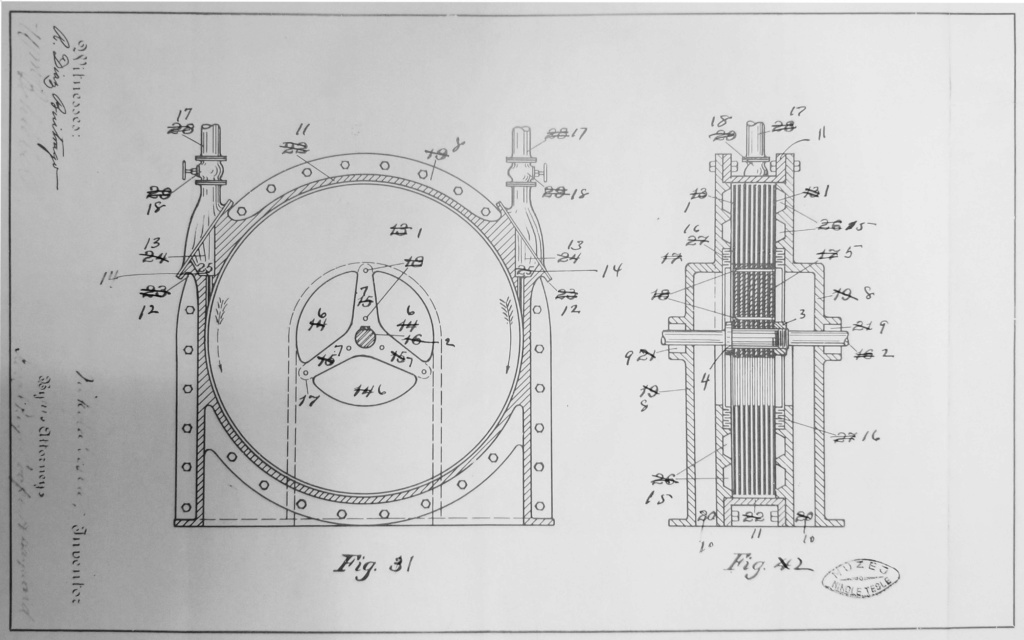

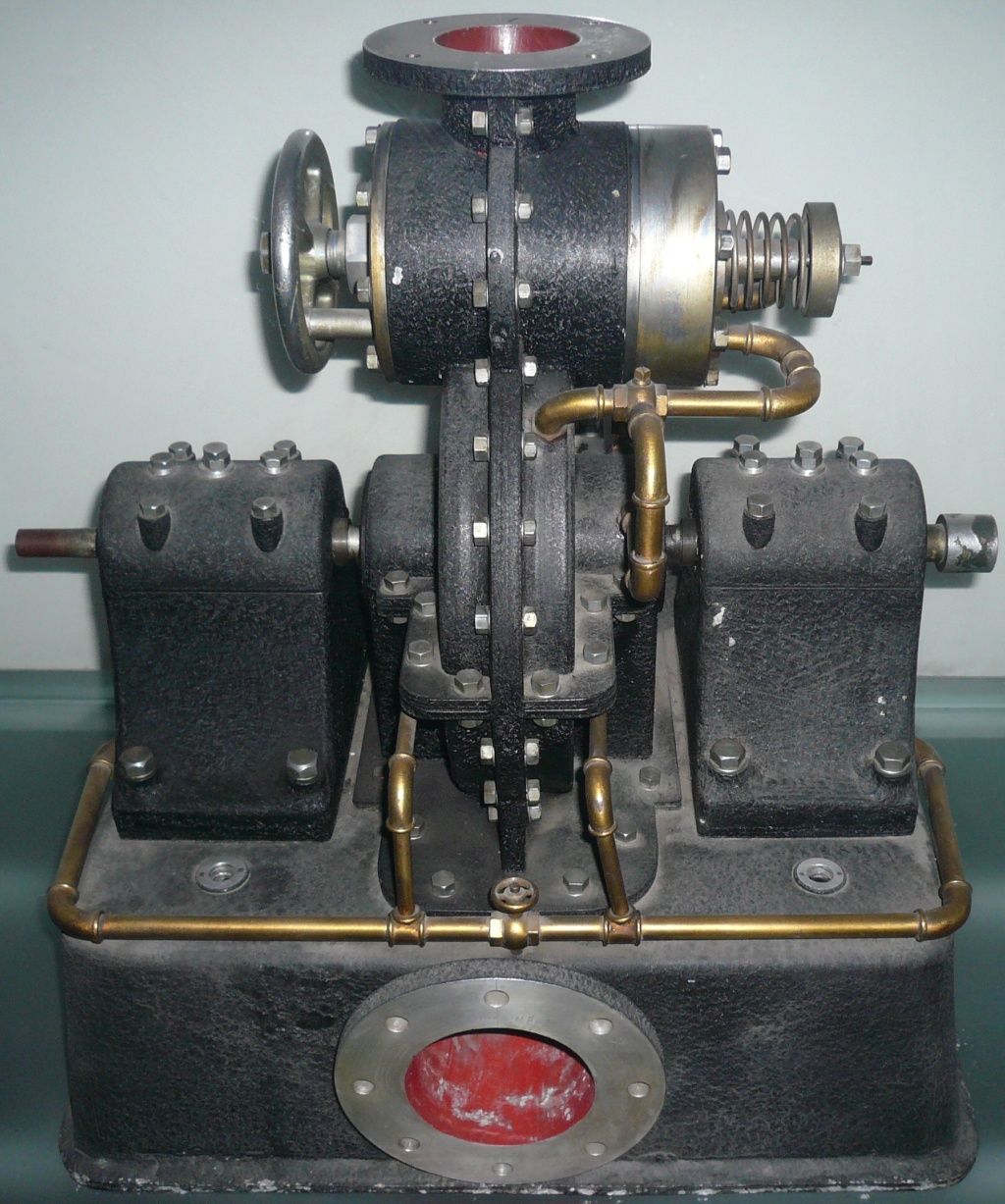

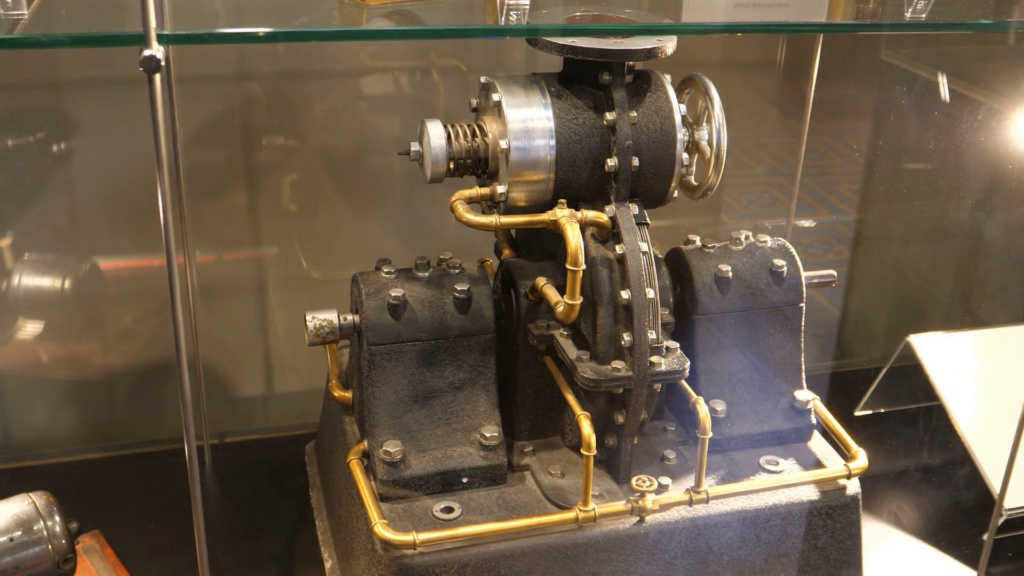

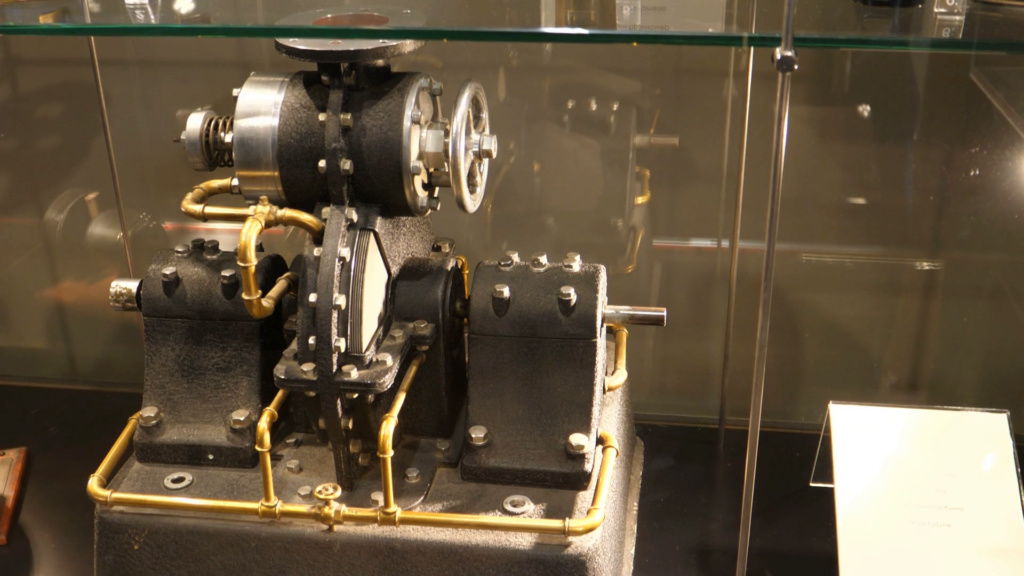

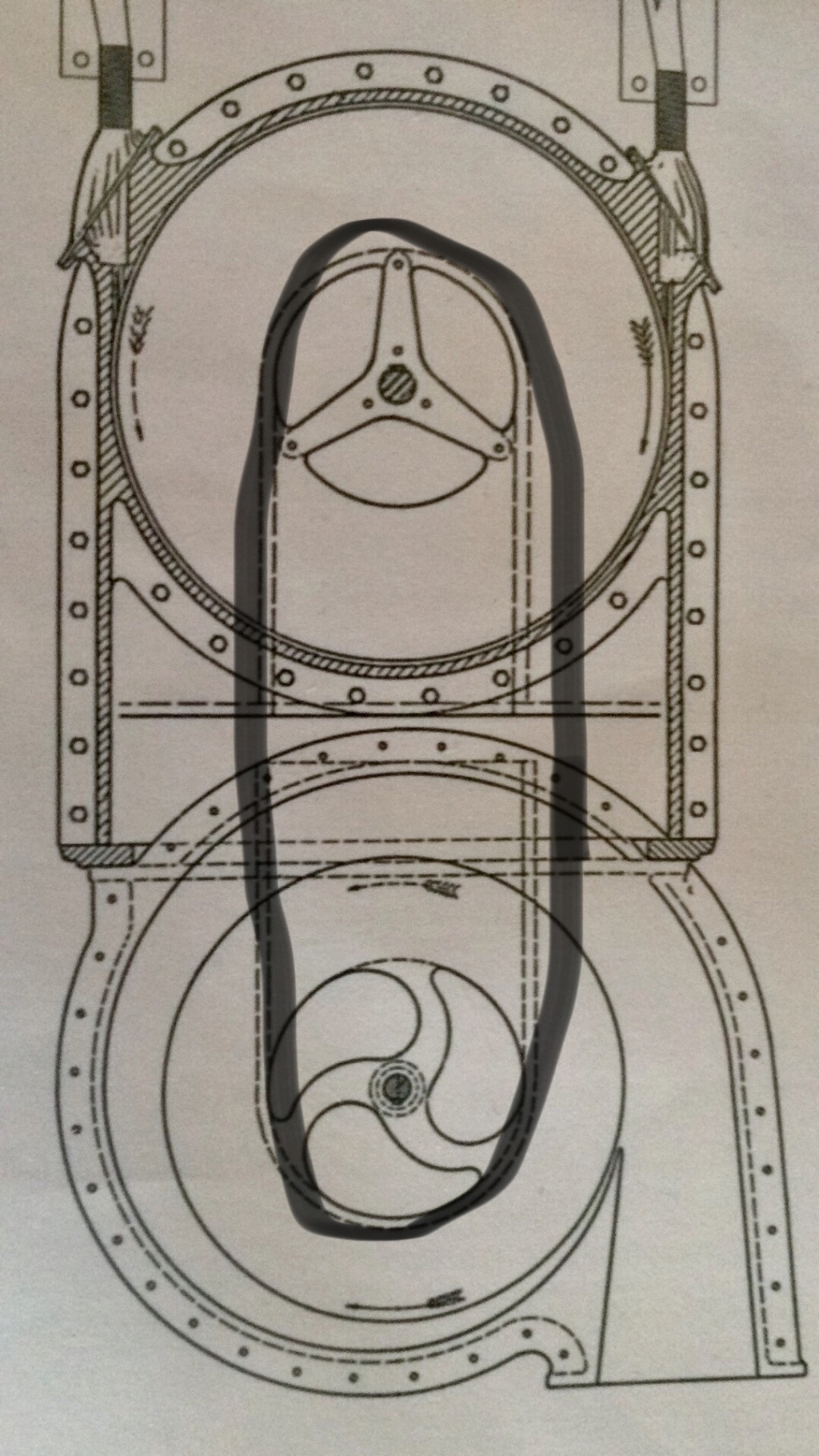

Mr. Tesla told me that his greatest pleasure was in his work, and that he could conceive no moment so exciting and rapturous as that connected with the discovery of a new principle which, when put into use, would revolutionize the work of the world. Take, for instance, the invention which brought forth the apparatus used in the transmission of power at Niagara Falls. Said he, as he took me to a great coil of wire wound about a stationary magnet, which was connected with the dynamo, and held above it a little glass globe in which was a steel wheel moving on a pivot: “I had been working upon that experiment for a long time, and this was the test. I knew that if I were correct that the wheel in this globe would revolve as soon as I turned on the electricity. It did revolve, and I knew I had discovered what would revolutionize the labor of the world. You can run all sorts of power by that principle. You can take power from Niagara and bring it to New York. The cars can be pulled by it, factories run, houses heated and dinners cooked. I cannot describe my sensation when I saw the wheel revolve. I thought I should go crazy, and I went to my laboratory and took some bromide of potassium to quiet me.

“It has been the same in some of my experiments with electric lights and other things. No; the greatest rapture one can have is to discover a new force or series of forces, which will reduce man's working necessities to the minimum. I do not believe in laziness, and I should like to see the loafer wiped from the face or the earth; but I want that those who are willing to work should accomplish their results with the least labor and in the best way.”

HOW TESLA WORKS.

As to Mr. Tesla himself, there is no harder worker known. He told me that he seldom slept more than four hours of a night, and during some periods not more than three. When in the thick of a new invention it is hard to sleep. His work is always with him and he says that his mind sometimes works in his sleep. He awakes in the morning to find that the problem which had worried him when he went to bed has been practically solved over night. He has always been a light sleeper. His mother died at seventy and she never took more than four hours' sleep. His father was a light sleeper.

Tesla is a peculiar worker. Failures do not trouble him. After he undertakes a thing and decides that it should come out a certain way, he keeps on experimenting and experimenting, believing in his success. He says that if he doubted his ability it would make him crazy. He seems to have a dual mind. He told me that he often found himself carrying on two trains of thought at the same time, and said that while he was talking to me he could see the figures of some of his calculations behind me and could carry them on at the same time.

TESLA'S NEW INVENTIONS.

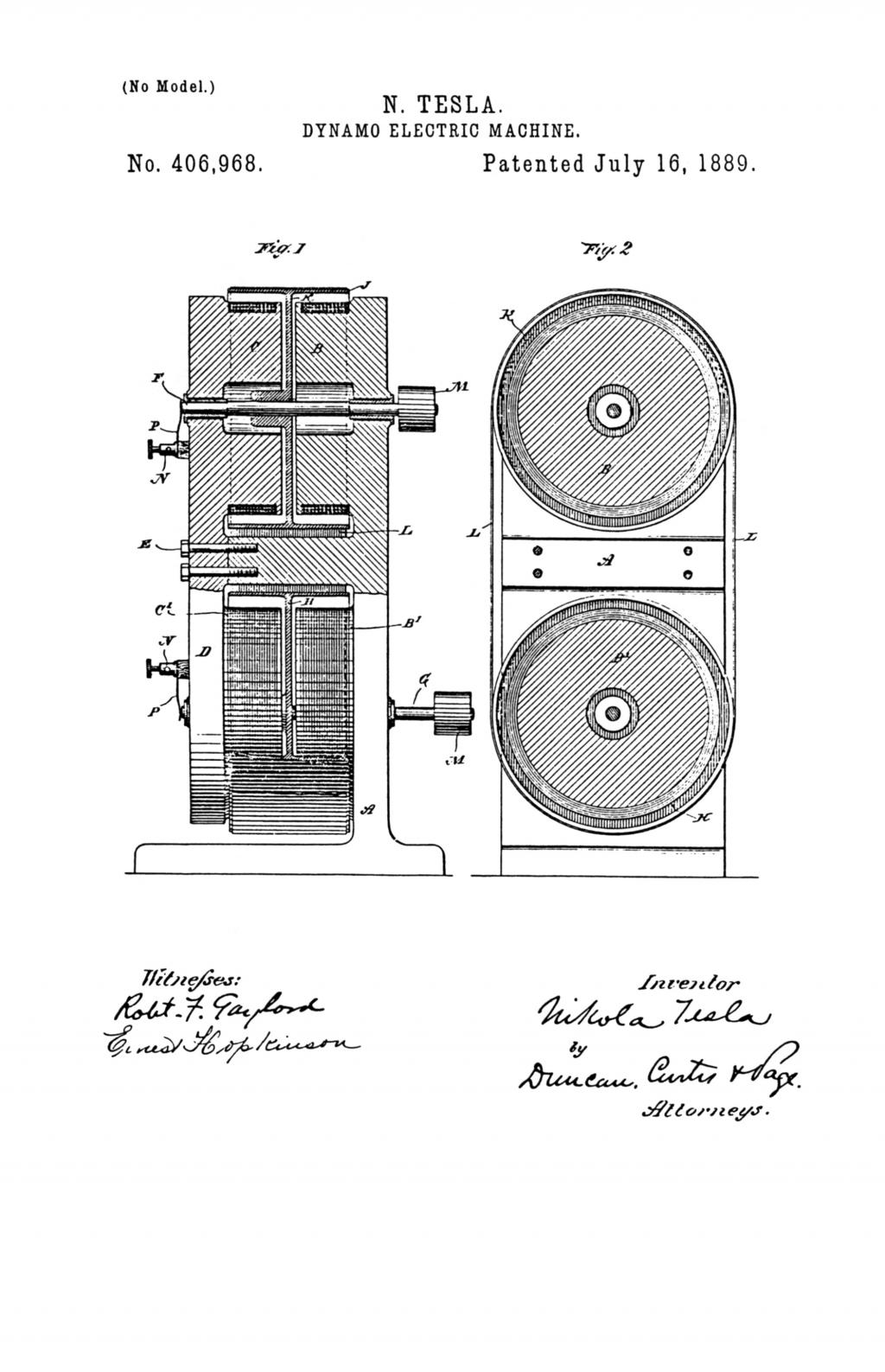

And now to Mr. Tesla's latest discoveries. If he has what he thinks he has he will revolutionize labor and give man greater benefits than have come from any inventor since the world began. Indeed, the statements made me tonight in the mouth of any other man would be a fair test of insanity. But many of Tesla's wild statements of the past have been verified by great working inventions. He said he could harness Niagara, and through his experiments in the rotary magnetic fields Niagara is now furnishing a power equal to that of tens of thousands of horses, and electrical works are being run by the same principle all over the globe. The New York subway, for instance, is founded upon it. Tesla demonstrated that wireless telegraphy could be done in 1893, and it is a question whether his inventions in that field are not prior to those of Marconi or De Forrest.

Tonight he told me that he had almost completed inventions by which he could send electrical power to any distance without wires, and that in any quantity, small or great. Said he:

“I have proved that power can be thus transmitted. Let us suppose I have my plant at Niagara and you are running a sugar factory in Australia; by my discoveries it will be possible to send you a hundred, five hundred or a thousand horsepower for your factory, and to supply the same regularly by the force furnished from Niagara Falls. Suppose you are traveling in the wilds of the Andes and make your camp on the shores of Lake Titicaca. By the outcome of this principle you may have telegraphed to you there instantaneous reports of the news of the world as it happens from time to time. You may cook your dinner over an electric fire thus transmitted, and you may have the same at will on any part of the globe. We shall be able to send power from place to place at will, and that at such a small cost that it will be industrially profitable.”

by Frank G. Carpenter

State, The, Columbia, SC

December 18th, 1904

New York, Dec. 17 — I give you today the substance of two remarkable talks with Nikola Tesla. The first I had in his laboratory on east Houston street nine years ago last September. The second was held in the Waldorf tonight.

The first interview was most interesting, giving a wonderful insight into Tesla the inventor and Tesla the man, but it was never published, for Mr. Tesla at its close, for business reasons, begged that I say nothing about him for months to come. I wrote out the notes, however, and laid them away, and when I met Mr. Tesla tonight I told him I how intended to use them. At the same time we had the extraordinary conversation about his recent discoveries and inventions as to the transmission of force, which I reproduce in the latter part of this article.

TESLA THE MAN.

First take a glance at Tesla the man. He looked more like an Italian savant than a hard working inventor when I saw him in the Waldorf tonight. He was in evening dress and was the most striking figure of the score of public men who stood about the lobby. Mr. Tesla is now 47 years of age and is in his physical and intellectual prime. He is tall and slender, his head is long, thin and intellectual, with a forehead high and full. He was born in Hungary and educated there, but he speaks English perfectly and is one of the most charming conversationalists I have ever met.

During my chat of some years ago he talked of his boyhood. His father was a clergyman of the Greek church, and Nikola was intended for the priesthood. He had a brother older than himself, whom the family considered much brighter. That brother died young, and this so crazed his father and mother that it took them long to realize the genius of Nikola. If he stood well in his studies his father's eyes would fill as he thought how much better, perhaps, the other son might have done, and whatever Nikola did was always compared with the possible work of the boy who had passed away. His first education was in the public schools of Gospich, and after that he went to the Real Schule at Karlstadt. As he went on with his studies he liked mathematics so much that he intended to fit himself to be a professor of mathematics and physics, and with that view studied at the polytechnic school at Gratz. He changed to the engineering course, and later on studied philosophy and languages in the colleges at Prague and Budapest. He has since been made a doctor of laws by Yale and Columbia.

Shortly after completing his studies Mr. Tesla was associated with the government of Austria-Hungary in the telegraph engineering department, where he invented several improvements. From there he went to Paris to be engineer of a large lighting company, and thence to the United States, where he was employed by Thomas Edison in his laboratory. His next position was that of electrician to the Tesla Electric Light company, and at the same time he established the Tesla laboratory here, from which his great inventions have come.

TESLA THE INVENTOR.

During my chat with Mr. Tesla I asked him when he first realized that he had the inventive faculty and he told me he had always been inventing something or other. When he was quite a small boy he made toy guns, which would shoot birds, and as he was the only one who could make them he supplied the boys of his neighborhood. He made clocks at eight or nine years and began to dabble in electricity before he was in his teens. His first determination to devote his life to invention came shortly after he went to London to deliver a lecture before a scientific society there. At this lecture he met Lord Rayleigh, the great physicist, and showed him some of the experiments. Rayleigh said that he had, undoubtedly, the faculty of discovery and that he would succeed as an inventor.

“Shortly after this my mother died,” said Mr. Tesla, “and I concluded to exert this faculty. Lord Rayleigh had said I possessed it and, upon examining myself, I believed him correct. I did not want to waste my powers on small things and I decided to strive toward something that would benefit humanity. I am working on an invention for the transmission of force. This invention will, I believe, revolutionize the world of labor. I am also working on electricity and I cannot remember when I was not working more or less in the direction of a successful flying machine. My idea, as to that, is along different lines than any yet proposed and I expect to see it realized. Indeed, we shall eventually have flying machines that will be large enough to carry crowds through the air. They must be large in order to succeed.”

These words were uttered by Mr. Tesla nine years ago. Today he says he has completed his force transmission invention, as will be seen by my Waldorf conversation, which follows. He has also done other things which he proposed in that interview. Remember it was before the time of the wireless telegraph, but he then said to me the following:

“I tell you, we are on the threshold of a new era. We have only begun to master the great forces of nature, and the inventions of the next few decades will be far superior to any of the past. What would you think of standing on the shore and telephoning to your friends in midocean? What of being in the centre of a room and making your whole body blaze with light? What of sending power to and fro over the earth at will and making it do its work anywhere and almost anyhow?

HOW IT FEELS TO INVENT.

Mr. Tesla told me that his greatest pleasure was in his work, and that he could conceive no moment so exciting and rapturous as that connected with the discovery of a new principle which, when put into use, would revolutionize the work of the world. Take, for instance, the invention which brought forth the apparatus used in the transmission of power at Niagara Falls. Said he, as he took me to a great coil of wire wound about a stationary magnet, which was connected with the dynamo, and held above it a little glass globe in which was a steel wheel moving on a pivot: “I had been working upon that experiment for a long time, and this was the test. I knew that if I were correct that the wheel in this globe would revolve as soon as I turned on the electricity. It did revolve, and I knew I had discovered what would revolutionize the labor of the world. You can run all sorts of power by that principle. You can take power from Niagara and bring it to New York. The cars can be pulled by it, factories run, houses heated and dinners cooked. I cannot describe my sensation when I saw the wheel revolve. I thought I should go crazy, and I went to my laboratory and took some bromide of potassium to quiet me.

“It has been the same in some of my experiments with electric lights and other things. No; the greatest rapture one can have is to discover a new force or series of forces, which will reduce man's working necessities to the minimum. I do not believe in laziness, and I should like to see the loafer wiped from the face or the earth; but I want that those who are willing to work should accomplish their results with the least labor and in the best way.”

HOW TESLA WORKS.

As to Mr. Tesla himself, there is no harder worker known. He told me that he seldom slept more than four hours of a night, and during some periods not more than three. When in the thick of a new invention it is hard to sleep. His work is always with him and he says that his mind sometimes works in his sleep. He awakes in the morning to find that the problem which had worried him when he went to bed has been practically solved over night. He has always been a light sleeper. His mother died at seventy and she never took more than four hours' sleep. His father was a light sleeper.

Tesla is a peculiar worker. Failures do not trouble him. After he undertakes a thing and decides that it should come out a certain way, he keeps on experimenting and experimenting, believing in his success. He says that if he doubted his ability it would make him crazy. He seems to have a dual mind. He told me that he often found himself carrying on two trains of thought at the same time, and said that while he was talking to me he could see the figures of some of his calculations behind me and could carry them on at the same time.

TESLA'S NEW INVENTIONS.

And now to Mr. Tesla's latest discoveries. If he has what he thinks he has he will revolutionize labor and give man greater benefits than have come from any inventor since the world began. Indeed, the statements made me tonight in the mouth of any other man would be a fair test of insanity. But many of Tesla's wild statements of the past have been verified by great working inventions. He said he could harness Niagara, and through his experiments in the rotary magnetic fields Niagara is now furnishing a power equal to that of tens of thousands of horses, and electrical works are being run by the same principle all over the globe. The New York subway, for instance, is founded upon it. Tesla demonstrated that wireless telegraphy could be done in 1893, and it is a question whether his inventions in that field are not prior to those of Marconi or De Forrest.

Tonight he told me that he had almost completed inventions by which he could send electrical power to any distance without wires, and that in any quantity, small or great. Said he:

“I have proved that power can be thus transmitted. Let us suppose I have my plant at Niagara and you are running a sugar factory in Australia; by my discoveries it will be possible to send you a hundred, five hundred or a thousand horsepower for your factory, and to supply the same regularly by the force furnished from Niagara Falls. Suppose you are traveling in the wilds of the Andes and make your camp on the shores of Lake Titicaca. By the outcome of this principle you may have telegraphed to you there instantaneous reports of the news of the world as it happens from time to time. You may cook your dinner over an electric fire thus transmitted, and you may have the same at will on any part of the globe. We shall be able to send power from place to place at will, and that at such a small cost that it will be industrially profitable.”

Comment